Keys for Meeting Supplement GMP Testing Requirements

A core concept across GMPs for many industries is scientific validity, and this is also one of the necessary requirements of the dietary supplement GMPs. For example, the purpose of an ingredient specification is to disclose scientifically valid methods and results for the tests, and these methods and results are used to verify the quality and identity of the material being sold.

Scientific validity means that tests must be suitable for what they are intended to measure. In a rapidly evolving industry, scientific validity is a core principle guiding our efforts to ascertain the identity, safety, and label claims of the material that millions of people take to support their health.

Here’s some ways NaturPro helps to ensure scientific validity…

To apply scientific principles to the measurement means that we develop a foundation of confidence in test results that accumulates only through repeated testing of viable hypotheses. During the process, we understand that like with many scientific measurements, sources of error exist which tend to increase with complexity. For example, complex samples containing thousands of chemical constituents (e.g., botanical extracts), and instrumentation methods that have a lot of variables all contribute to our bank of “known unknown” and “unknown unknowns.”

Testing using any single method can be an educated guess as an answer to a different question, especially for labs that may only sporadically test a given matrix with a single type of test.

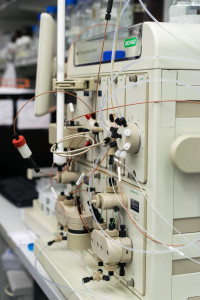

Today’s analytical technology to measure analytes in complex mixtures is way ahead of the not-too-distant past, but now we understand a mitigating factor: that with greater power and resolution comes an increasing number of factors that may cause test results to be inaccurate or imprecise.

Today’s analytical technology to measure analytes in complex mixtures is way ahead of the not-too-distant past, but now we understand a mitigating factor: that with greater power and resolution comes an increasing number of factors that may cause test results to be inaccurate or imprecise.

For example, it can be difficult to account for systematic error associated with dirty chromatography columns or non-optimal instrument conditions. Inaccurate purity data on reference standards (due to either inaccurate standard purity values, or unaccounted-for degradation during storage) are also a common sources of error — when we are simply trying to figure out the “actual” composition of a material. Another source of error arises from the calculation of the results; for example, moisture can account for a certain amount of the measured weight of both samples and standards, which is often simply estimated, even if it is accounted for.

What more does supplement testing and Star Wars have in common?

Other sources of error in testing can be chalked up to incomplete extraction and isolation during the sample preparation. The subject of dissolution is an interesting one. For example, it is a common assumption that when a sample “dissolves” during HPLC sample prep, then it is fully “ionized” and thus is not strongly bonded to any solid particles (which then often get caught on the filter and not pass into the detector).

If both standard and sample dissolve to the same degree, no problem! But (unknown unknown) error due to lower than expected ‘percent recovery’ creeps in when your sample is prepared with heat and time, becoming different compounds and binding differently to the protein-fat-and-sugar matrix of a biological product. So the analyte that you are trying to extract into another phase is often a lot easier using the pure, unbound. chemical reference standard — leading to a difference in percent recovery. So chemical reference standards are best complemented in testing with an additional control being the original, authentic botanical reference — yes a whole plant part, taken from the same source as the raw material in question. Sounds easy, but its actually not for a lot of people.

Then compound the sample preparation challenges with the high heat and pressure applied by an analytical instrument like HPLC, where more chemical reactions can happen in the complex sample to degrade what you are measuring, all while your pure reference standard survives nicely to the detector. (Theoretically, this scenario can also happen the other way around, where the matrix stabilizes the analyte better than the standard solution under the HPLC conditions.)

Exciting stuff, all this mystery, which we eventually find answers to through validation and repetitious testing. While it’s difficult to predict analytical uncertainty, the point is to control it to the extent possible, hopefully to within 5-10% of your expected result — not bad compared to the 20% tolerance limit required by pharmaceuticals.

Exciting stuff, all this mystery, which we eventually find answers to through validation and repetitious testing. While it’s difficult to predict analytical uncertainty, the point is to control it to the extent possible, hopefully to within 5-10% of your expected result — not bad compared to the 20% tolerance limit required by pharmaceuticals.

The practical question facing suppliers and manufacturers is how to ensure your specification accounts for testing variance? One solution commonly opted for in the short term is surprisingly simple: add the testing variance to the label or spec requirement, to ensure a high statistical probability that the material won’t fail due to inherent imprecision of the test.

The implications of an imprecise test often means that manufacturers are forced to add an ‘overage’ of material, which essentially makes the cost of the material 10% more expensive for every 10% difference in test results.

Scientific validity in QC testing for supplement all too often is discussed not on a daily basis, but when the cost of “mistakes” has finally sunk in. Many a product formulator saw hours and months of work go down the drain due to quality testing failures, and everyone involved in product development can testify to the measurable waste of time and resources that result from testing failures, which can include both the approval of bad material, as well as the rejection of good material.

Five ways NaturPro helps to ensure scientific validity…

Here is a short list of some practices that QC units can perform to achieve scientific validity as per GMPs:

–Review your lab’s methods for their suitability for the intended purpose. There are good independent labs out there that will share method information, and answer your questions. Always ask whether the sample is being tested in triplicate and request to receive the individual values.

–Review the documentation on the reference standard, specifically the methods and results of the testing used to determine its purity. When was the standard made, when was its purity last tested, and how was it stored in between?

–Blind your sample so your lab does not know what value to expect.

–Test control samples (samples that do not contain the suspected analyte, OR samples that you previously sent to the same lab).

–Work with labs that can demonstrate having worked to some basic degree to optimize/validate the method.

Sounds like costly work, but not so much when put in perspective of the potential costs. With transparency among customer, supplier, and lab together, a little teamwork goes a long way to reduce the costs and maximize the benefits of quality systems.

By: Blake Ebersole

This article was first published in Natural Products Insider in June 2013

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.